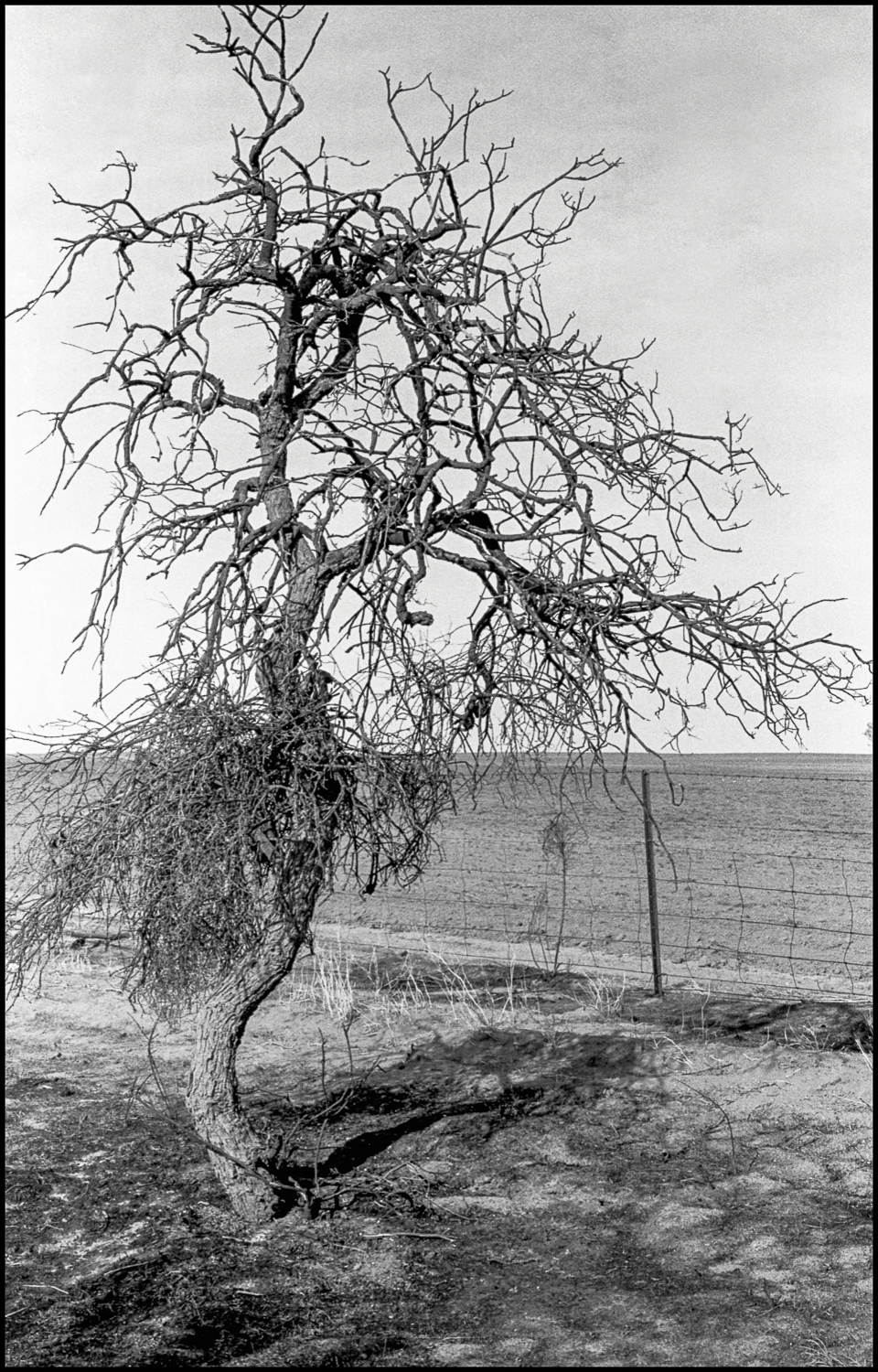

After seeing how successful the history section worked when it was integrated into the contemporary photos in the 2018 Mallee Routes exhibition at the Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery, I remembered that I had some black and white 35mm negatives of the Murray Mallee in my photographic archives. Over the weekend I went back and looked at the contact sheets of the pictures from my initial exploration of the South Australian Mallee country in the late 1980s. I was curious to see these 35mm photos, and to assess if they would be suitable to construct a history section in the Mallee Routes exhibition at the Murray Bridge Regional Gallery in early 2019.

I have not seen these 35mm pictures since they had been sleeved and filed away in the 1980s. I had previously only looked at the large format b+w ones that I had made with the 5×7 Cambo on the same road trips, when I was selecting a couple of my images for the history section of the 2018 Swan Hill exhibition. This land had been permanently altered for agricultural production.

From what I could judge from looking at the contact sheets of these 35mm images, these were made on a few day trips to the Mallee in the VW Kombi. I recall that most of them were made with Kodak Tri-X film using a Leicaflex SLR, rather than the 35mm Leica M-4 rangefinder, that I normally used. Surprisingly, I discovered that there were no medium format contact sheets of photos of the Mallee country in the archives.

Over the weekend I scanned a selection of these 35mm images, and then started to assess them on the computer screen to see if they could be linked to the current malleeRoutes project in some way. Judging from the contact sheets the day trips were a simple photographic exploration of the Mallee, and I never returned to photographically explore this country more deeply. There was no photographic project involved.

The Mallee lands were new to me then, as I had only lived in the cities of Melbourne and Adelaide after migrating to Australia from New Zealand in the early 1970s. I just drove along the country roads in South Australia taking snaps along the way, apart from staying a weekend in Mantung with friends from Flinders University, which is where I made most of the 5×7 Mallee pictures. I knew little about it apart from most (estimates are around 80%) of the mallee being cleared for agricultural development, beginning in the 1880s.

The 35mm snaps were a noting of what I found to be most striking about this part of the Mallee landscape. What caught my eye were the ruins, the harshness of the landscape, the limestone, the silos, the railway lines, and the dryness. This was marginal land with limited rainfall and grass, and so the colonial farmers were dependent upon underground water with the opening up the Murray Mallee for primary production. This was a country where the dreams of the settlers could quickly turn to nightmares from the overstocking, rabbits, and droughts. Droughts are a normal part of these marginal lands. These are damaged landscapes.

Marginal landscapes is a more suitable description for this kind of work as opposed to New Topographics, which refers to the 1975 exhibition in the US, ie., at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, (featuring Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore and Henry Wessel, Jr). This exhibition referred back to the 19th century topographic photography in the US ( eg., William Henry Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan). The perspective of Adams and Baltz, towards the transformation of western spaces by real estate developers to build tract housing developments and industrial parks was the language of a formalist, geometric abstraction of a disengaged, autonomous Modernism. Their emphasis was on the geometric organization and composition of the picture, and its formal beauty and elegance.

Contemporary photographs in the topographical style in the second decade of the 21st century cannot be new anymore nor unconsciously adopt the language of a formalist modernism. Nor can the contemporary topographical style be just be new landscape photography, since the topographical style is a particular approach to the landscape within a plurality of photographic approaches to the landscape. It is a perspective that explores the negative human relationship to the land with an interpretative documentary as opposed to a poetic approach.

[…] have been going through my 35mm archives looking through images from the 1980s to include in a possible artist book for the […]

[…] further in relation to the Mallee Routes project?I have decided in the affirmative. It would link with the past and compliment the colour […]